In brief

- We analyse a new dataset of transactions from 27,182 Capitec customers.

- Boxer has a ~9% spending share among customers earning less than R15k pm.

- Boxer achieves the second-highest average transaction value among its competitors, but the lowest transaction frequency.

- Boxer’s discounter model seems to limit the proportion of grocery spending it can capture from individual shoppers.

- Store count will continue to be the dominant growth driver for Boxer.

- A stronger PnP may be a challenge to Boxer, and a separate Boxer introduces additional complexity for minority shareholders…

Pick n Pay is in serious trouble. In February, the group announced plans to raise R4bn from shareholders and to list a portion of its best-performing division: Boxer.

At Reveal, our goal is to use alternative data to give investment analysts a deeper understanding of their investment universe. This universe may soon include Boxer.

That said, our traditional spending data is generally representative of a higher-income customer and doesn’t offer the best view of a Boxer shopper, who is typically from a lower-income bracket.

So, we went shopping…

We acquired anonymous and de-identified transaction data for 27,182 Capitec customers from a service provider that facilitates KYC validation for lenders, mobile operators, municipalities, landlords and the like.

The median income across the sample was R16,369 pm, with an average age of 31. (We calculate income as the average cash inflow per month to the account.) As the charts below show, the sample is large and well balanced, with a good spread from very low to very high-income earners.

SAMPLE SIZE BY INCOME BRACKET

SAMPLE SIZE BY AGE

When it comes to transactions, there are 19 million in the sample. From those, we extracted 575,600 purchases at Boxer, Shoprite, Checkers, Usave, PnP and Spar, over the four months ending January 2024.

Our research has historically focused on national retailers like those listed above, but the topic and the data allowed us to explore spending at less-formal grocery and food merchants, too. These include spazas, superettes, cash-and-carry stores and other grocery retailers.

The exact number and make-up of the merchants in this category are difficult factors to evaluate. Stores range from significant competitors like KitKat Cash & Carry, to hundreds of small spazas and supermarkets like Hamza Supermarket near Mbombela. (Click the link. It’s worth it.)

We refer to this collection of stores as ‘Less Formal’ because:

- It’s not a collection of purely informal traders, so it’s more accurate;

- There’s a range of reasonably large and very small stores;

- The category excludes cash transactions. By design, our data only reflects swipes or taps. Cash-only stores are generally informal in nature.

In total, purchases made by 12,600 customers at these less formal retailers added a further 82,247 transactions to the total transaction sample.

Across the whole sample, customers spent anything between R500 and R2,800 each month at the merchants considered in the analysis. Compared to the midpoint of their income bracket, this equates to 5–21% of their grocery wallet.

MONTHLY SPEND BY AGE AND INCOME BRACKET

SPEND AS A PROPORTION OF INCOME BRACKET MID-POINT

Observations:

- A 30-year-old customer earning ~R6,000 pm spends roughly 10% of her income (R691) at the retailers included in this analysis. By contrast, her contemporary earning ~R17,500 pm spends 7% of her income at these stores (R1,306). From the outside (I’m not that young!) these amounts appear low. But remember that this is not an exhaustive analysis of every possible channel of purchasing groceries – there will be some spending at merchants not included. And, importantly, our analysis excludes all cash purchases.

- Income is a more significant determinant of total spending than age. The average change in spending across successive age brackets is 6.5%, whereas the change across successive income brackets is 25%.

- This analysis does not include Woolworths because transaction data is unable to distinguish between clothing and food-related purchases. Woolworths’ clothing division is skewed towards a lower-income consumer but their food division is not. Since this report is focused on lower-income grocery spending, including spend at Woolworths would increase the food spend of higher-income consumers even further, creating an even more extreme contrast between lower and higher income brackets.

Who shops at Boxer?

Boxer’s operating model differs from PnP’s. As a grocery discounter, it offers a comparatively narrow range of products – about 3,000 compared to 8,000+ in a typical PnP supermarket – with the commitment that these products will always carry the lowest price.

Even though Boxer has outperformed PnP’s core supermarket business for many years, it has only recently been separately reported on. Now that shareholders can disentangle Boxer from the core, we can see that the chain has reported sales of R34bn for the 12 months to Aug 2023. During the same period, the division posted growth of 17.1% – 11.9% of which came from expanding the store footprint.

The chart below shows the grocery spending share split for the 27k customers in the sample, by age and income bracket, at the six grocery chains in the analysis, as well as at the less formal stores.

Observations:

- Boxer’s share of total spending is greatest among low-income consumers (~10%) and it decreases consistently as income increases. Spending share is relatively stable (~9%) among customers earning less than R15k pm and declines more rapidly in higher-income brackets.

- In general, spending share is relatively stable across age brackets.

A key factor that determines market share is average transaction value (ATV), or ‘basket value’. ATV is an important driver of profitability: given mostly comparable products, all else equal, the more a customer spends per visit, the greater the absolute profit.

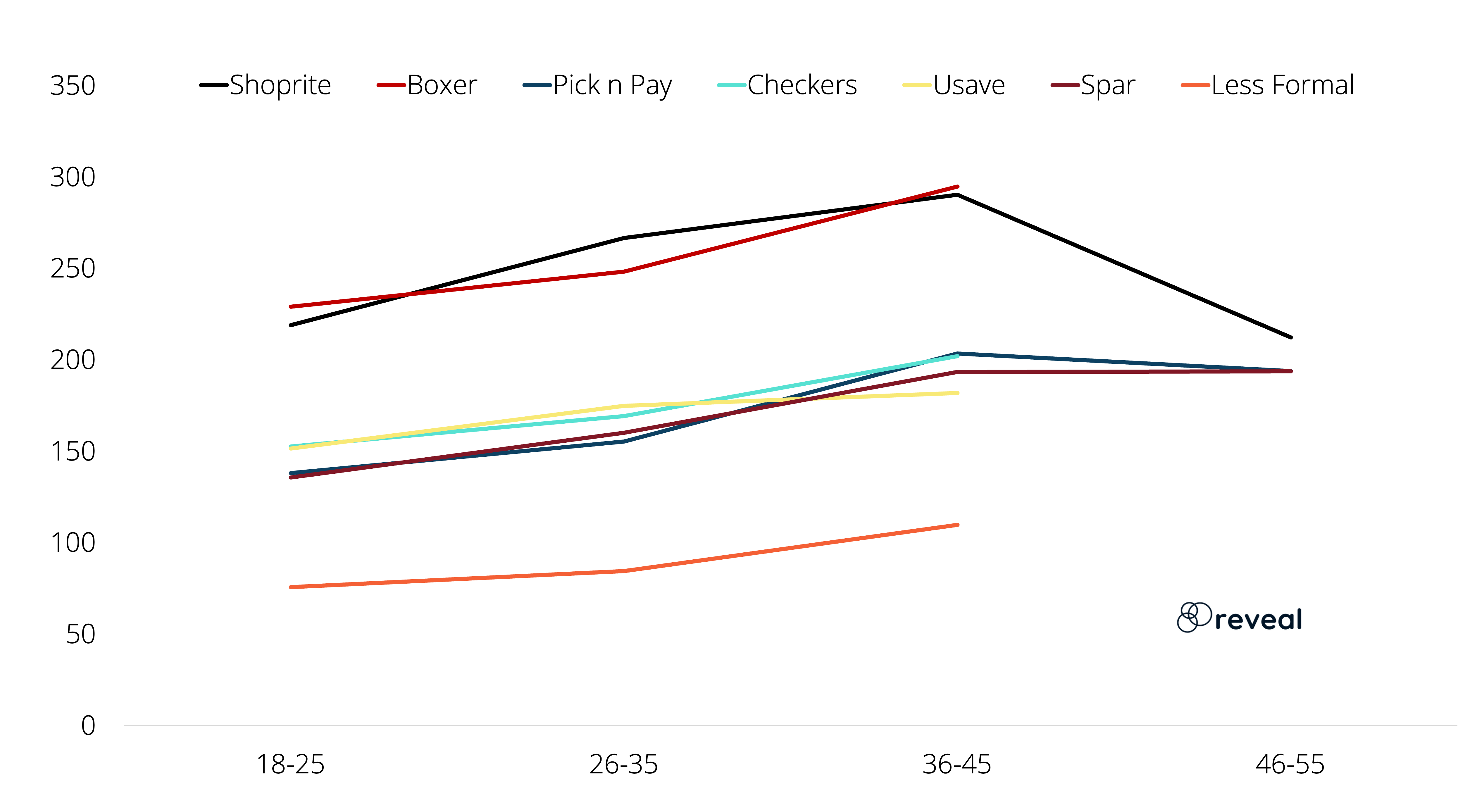

The following charts compare average transactions. In the first, we hold age constant and compare across income brackets. In the second, we compare across the age spectrum.

AVERAGE TRANSACTION VALUE BY INCOME BRACKET: CUSTOMERS AGED 25-35

AVERAGE TRANSACTION VALUE BY AGE BRACKET: CUSTOMERS EARNING R7.5–10K PM

Observations:

- ATV across the board increases as income increases. When it comes to age, ATVs peak among customers in the 35–45 bracket and then decline.

- In general, Shoprite has the highest ATV for each income and age bracket.

- Boxer’s ATV falls between Shoprite and Checkers for the age bracket shown, but in other age brackets, Boxer has the highest ATV.

- In most income brackets, PnP’s ATV is the second lowest, behind Usave. Its position improves among older customers, although there are more gaps in the data and fewer comparisons.

- Transactions at less formal stores have the lowest value on average.

Now let’s segment market share for a major cohort of Boxer shoppers aged 25–35 with incomes ranging from R7.5–R10k per month.

Controlling for age and income, this tells us:

- Shoprite attracted the most shoppers in this segment, followed by Spar (-5%) and PnP (-13%)

- At R248, Boxer’s ATV is just 7% lower than Shoprite’s, whereas other major retailers’ ATVs typically range between R155 (PnP; -42%) and R175 (Usave; -34%). This is a positive for Boxer, given that it’s a limited-range discounter and Shoprite is a full-range supermarket.

- Boxer has the lowest purchase frequency (1.7x month) – slightly lower than Usave. Customers shop most often at Spar (2.5x) and at less formal stores (2.4x).

- This method of decomposing market share is useful to highlight the different ways that customers engage with a retail chain. Look at Shoprite and Spar, for example. Both serve a similar number of customers (Spar 5% fewer); Shoprite attracts a much higher ATV (+60% vs Spar); while Spar customers shop 24% more often. The result is that Shoprite’s market share is 42% higher than Spar’s

- [42% = (1-0.05) *(1-0.4)*(1+.24) - 1].

To sum up this section, we’re positively surprised by Boxer’s average transaction value. As a limited-range discounter, customers spend almost as much at Boxer stores as they do in Shoprite supermarkets, which have a much wider product offering.

How does store count affect these numbers?

Boxer has a smaller store footprint than competitors like Shoprite, which is reflected in its lower market share. Surely it just needs to grow its store footprint then?

It’s not that simple. Based on the latest store lists from each retailer’s website, we estimate that Boxer has 281 superstores. (For the purposes of this analysis, we’ve ignored other store types in the count, like liquor, clothing, building etc.) Shoprite (577), PnP (617) and Spar (940) all have much larger store bases.

It’s also common to hear about provincial strongholds in the retail landscape. Boxer’s origins are in KZN and it has the most stores in that province, with comparatively few in Gauteng and the Western Cape.

Side note: we’re surprised that Spar doesn’t have a greater bias towards KZN. It’s often suggested that Spar has a strong reliance on this province, but its store distribution does not suggest any greater reliance than its major competitors.

How do we take the provincial differences in store bases into account? Do we even need to? Maybe, instead of focusing on all customers, let's narrow the focus to customers who shop at Boxer and at the other retailers, and compare the relative proportion of their grocery spending. Put differently, someone who shops at Boxer must be close to a Boxer store. Can we compare how these users shop at Boxer to how other customers shop at other stores?

To visualise this, let’s keep age constant and consider customers in the 25–35 bracket. The chart below compares the proportion of total spend at each retailer. We call this 'loyalty’ – a customer's share of total spend at a retailer.

For example, customers earning less than R5k per month, who shop at Shoprite, spend 45% of their total spend there. (The chart shows that Shoprite attracts the largest proportion of total spend across all income groups.)

LOYALTY BY RETAILER: CUSTOMERS AGED 25–35

At a glance, the chart appears similar to the market share charts above, but it’s actually showing something quite different: how much a customer spends at a retailer, relative to all the other retailers they also shop at.

Let’s go to Boxer again as an example. We’ve already shown that Boxer’s market share across all income demographics is ~9-10% (p 4) – this chart shows that Loyalty among its customers ranges from 25–35%.

(It’s worth considering the number of customers shopping at each retailer. Although this chart shows that Boxer’s loyalty is relatively stable across income brackets, earlier charts showed that its market share falls abruptly in brackets above R15k pm. The implication is that the number of customers who shop at Boxer in those brackets falls rapidly. The loyalty shown above simply demonstrates that the few wealthy customers who do spend at Boxer, spend c20% of their total grocery wallet in the store.)

It's interesting that for the two lowest income brackets, Boxer’s loyalty is most like Usave’s and the Less Formal retailers. Usave is also a low-cost, limited-range discounter; and although the ‘Less Formal’ category is comprised of many individual retailers, the spazas and superettes there are more likely to fall into same category of discount retailers than wider-range supermarkets.

It’s encouraging that the data shows such high consistency between these retailers at the lower-income end of the market. More importantly, it affirms the role that a limited-range discounter fulfils for its customers. By offering only a limited range, these retailers cannot fulfil as many needs as a wider-range supermarket. A limited range can boost profitability… By aggregating demand within a product category, operations can be simplified and volumes can be boosted, along with the retailer’s purchasing power with suppliers. But loyalty to a discounter will always be lower.

With a loyalty at 40%+, Shoprite sets the standard in this space. But the data shows that even PnP has higher loyalty in lower-income categories than Boxer and Usave. (It is known that PnP has different ‘types’ of stores under the single brand, something it was trying to solve under Project Ekuseni.) This supports the notion that loyalty to a discounter can probably be capped at ~30%.

Finally, look how similar shopper loyalty is for PnP and Checkers in the income brackets between R15-60k pm, where its supermarket formats are most competitive.

To sum up this section, our analysis suggests that Boxer performs very well in the market that it operates in. But with a limited range of discounted products, the retailer is ‘boxed-in’ when it comes to how much spending it can attract from customers.

With that in mind, it’s unlikely that Boxer will be able to capture a significantly larger spending share from customers who are already shopping at its current stores.

So, will unbundling Boxer save PnP?

This analysis demonstrates Boxer’s pedigree as a retailer. Lower-income customers spend as much at Boxer as they do at Shoprite, which is the market leader in this category. However, as a limited-range discounter, Boxer is approaching natural thresholds as to what this retail format can extract from its customers. Store growth will therefore continue to be the most significant driver of growth.

Boxer has 70% as many stores as Usave, the most obvious discount competitor, and 50% as many as Shoprite. If store growth continues at ~10% pa, then space may be a reliable avenue of growth for Boxer for the next three to five years. A much larger store base will require a much more expansive supply chain.

Supply chain and minority investors

The analysis has yet again shown how formidable the Shoprite Group is: three distinct brands with targeted consumer segments and differentiated retail models, each leveraging a single, integrated supply chain. The scale of this supply chain drives efficiencies that are reinvested elsewhere to continuously improve those efficiencies.

On the other hand, we understand that PnP and Boxer operate relatively separately, with different distribution infrastructure, logistics, merchandising and other functions. The allure of Project Ekuseni was that it attempted to replicate Shoprite’s strategy of three different consumer propositions and the possibility of the supporting supply chains to integrate, which could have led to a more efficient, profitable business.

PIK (to distinguish the group from PnP supermarkets) now plans to list a minority shareholding in Boxer to raise capital. We believe this would introduce complexities for minority Boxer shareholders when it comes to the dark art of allocating returns associated with a retailer’s supply chain. For example, how will a minority shareholder in Boxer know whether rebates by suppliers of products sold by Boxer are fully allocated to Boxer, as opposed to cross-subsiding PnP purchases from the same supplier?

Is growth zero-sum for PIK?

We’ve written extensively about the market share shift from PnP to Checkers among higher-income consumers. But PnP’s challenges are not limited to this segment alone. This analysis is a reminder that PnP’s weakness is a boon to other retailers, including Boxer, which has likely been (and continues to be) a major beneficiary.

Investors backing a recovery at PnP should acknowledge that this might impact Boxer’s growth prospects. In a consumer market without any real growth, a better-performing PnP implies slower growth for Boxer…

What we know now

Our original mission was to leverage alternative data to learn more about Boxer. In doing so, we’ve shown that Boxer trades well against the market leader in lower-income consumer categories. As a discount retailer, there is some evidence that Boxer is reaching the limits of what its model can offer existing customers. Expansion into new territories is a viable growth driver for Boxer over the next few years.

A larger store base will require Boxer to build a more complex supply chain, most likely into territories where PnP already has infrastructure. More sharing of infrastructure may be required and is perhaps necessary to match peer-group efficiencies. However, a separately listed Boxer raises questions about how the costs and returns of building and operating an integrated supply chain will accrue to minority investors.

Finally, in a weak economy and a relatively concentrated market, analysts should be careful not to double-count growth going forward. Boxer has grown ahead of the market in the past, partly because PnP has lagged. Going forward, if investors believe in a PnP recovery, the outlook for Boxer must be more modest.